Late one summer evening, just as the day’s monsoon rains receded, a 68-year-old activist named Robin Silver climbed through a barbed-wire fence outside Tombstone, Arizona. He was headed for a riverbend near the site of a ghost town locals know as Charleston. It had taken Silver most of the afternoon to cover the short distance from the nearest road, his path obstructed by pools and clots of dislodged cottonwoods—evidence of the season’s capricious flash floods.

At the bend, Silver stopped and peered up- and downstream. Beyond him in both directions ran the San Pedro River, its banks a ribbon of greenery unfurling gently through the red desert. “This is where the Charleston Dam site was,” Silver said. “Where it would have gone across.” Commissioned in the late 1960s as part of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s vast network of reservoirs and canals, the proposal was scuttled in 1977 over concerns about its cost and impact on the river. A relatively minor move in the bureau’s remaking of the American map, Silver explained, it nevertheless granted the San Pedro a rare fate: Today it remains one of the last major free-flowing rivers in the Southwest.

Silver unshouldered his pack. “We come into places like this and dam the river, farm the fields, kill everything,” he said. A group of Turkey Vultures erupted from the canopy. “But this place still has a shot.”

Silver is a co-founder of the Center for Biological Diversity, a national organization that advocates for endangered species. In the decades since the Charleston Dam was defeated, CBD, local Audubon chapters, and other advocates have waged a near-constant battle to save the San Pedro and its riparian habitat, which serves as a breeding ground or migratory stopover for hundreds of bird species. They have won multiple lawsuits, arguing that the San Pedro is a vital but increasingly fragile island of biodiversity. “You hear us use the word last a lot,” Silver said of the San Pedro. “We’ve dammed and diverted the Rio Grande, the Gila, the Agua Fria, the Santa Cruz, the Colorado. They’re gone.”

In recent years the conflict over the river has shifted upstream, to the Army’s Fort Huachuca and the military community built around it, Sierra Vista. As the small city’s population has exploded, nearly doubling to more than 40,000 since 1980, so has its water consumption, damaging the aquifer that supports the river and drying up wetlands and tributaries. Since 2016 Silver and allies have been embroiled in a legal fight on two fronts: a suit alleging that the fort concealed its unsustainable water use for years, and an effort to block a massive housing development whose financier has ties to the Trump administration. But while the cases are similar to others they’ve won, river advocates have new reason to worry. The administration’s sweeping changes to the Endangered Species Act and Clean Water Act—historically two of the most effective tools for protecting the San Pedro—appear to have weakened the river’s defenses, even as it strains under a climate granting up to 40 percent less rain than decades ago.

A lifelong Arizonan, Silver was beginning to contend with the reality that the river might be on the verge of collapse. This was one reason he’d wanted to visit the dam site; seeing the undeveloped bend helped remind him of what had been overcome and what could still be lost. Standing in the river, he brought up the cautionary tale of the nearby Santa Cruz. Once a vibrant mosaic of trout holes and willow brakes, the Santa Cruz is now mainly a desiccated stretch of sand—its waters drained as the city of Tucson grew around it. “We stopped the Charleston,” Silver told me. “But these things never really die.”

K

nown through history as “Beaver River” and the “Valley of the Shadow of Death” for its confusing array of pools and biting insects, the San Pedro has long served as a rare shaded route through the scorching and disorienting Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts. Ranchers still sometimes happen upon spear tips in the river from the last ice age, when Clovis people hunted mammoths along its banks.

From its headwaters in Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental to its confluence with the Gila River, the San Pedro runs dry in stretches and for parts of the year. It erupts in mid-summer, when deluges of monsoon rain scour the high mountains, gushing through its tributaries. The floods, like the desert, are volatile, and every year yields a different river. In a Nature Conservancy survey this past June, only 46 of the river’s 174 miles were wet. The river does not cease running, however; it merely drops a few feet from view. Below ground it flows on, seeping through sands and gravel, the riot of vegetation along its banks evidence of the hidden waters.

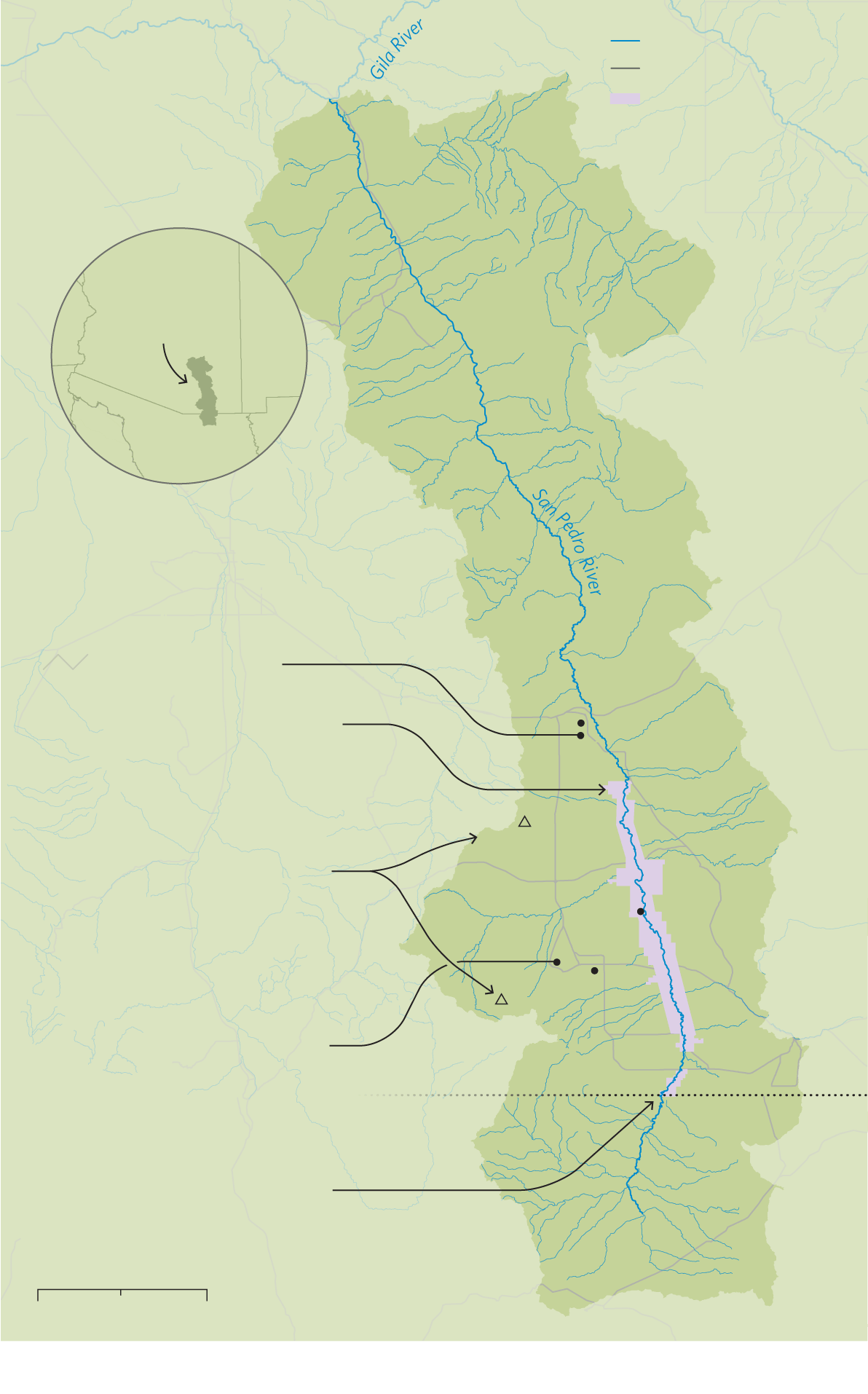

San Pedro

River Watershed

River

Major road

San Pedro Riparian

National Conservation

Area (SPRNCA)

ARIZONA

San Pedro River

watershed

SONORA

The planned 28,000-home Villages at Vigento would destroy tributaries and use about 2 billion gallons of water per year.

Benson

The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area was the first Globally Important Bird Area in the country.

Whetstone

Mtns.

Growing communities capture groundwater from rain and snow in the Whetstone and Huachuca Mountains, a vital water source for the San Pedro.

Charleston

Sierra

Vista

Pumping by Fort Huachuca, one of the area’s biggest water users, began harming the river as early as 2003, per a leaked report.

Huachuca

Mtns.

ARIZONA

SONORA

U.S.-Mexico border

A new border wall segment across the San Pedro will cut off wildlife and could act as a dam for monsoon floods.

20 Miles

0

10

Map: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda

Although naturally occurring, these buried stretches are expanding and drying out as Sierra Vista and surrounding communities grow. Situated between the river and mountains, the city sucks up the groundwater that would otherwise seep into the San Pedro from below. According to a 2014 report to Congress, the Sierra Vista area is depleting its aquifer at the rate of about 1.6 billion gallons each year. With more wells capturing more water, stream flows have become increasingly dependent on rain, even as the Southwest suffers one of the harshest megadroughts of the past 1,200 years—and the first fueled by human-driven climate change. Some scientists are convinced that, absent a radical intervention, the San Pedro will run dry by century’s end. “This river is already teetering on the edge for natural reasons,” says Mark Murphy, a senior water scientist with the engineering company NV5 who has provided expert analysis to the legal team for San Pedro advocates. “It can be pushed over it so easily.”

One of the few stretches that remain wet year-round lies just east of Sierra Vista, in the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. Around 350 bird species have been recorded at SPRNCA, among them Vermilion Flycatchers, Gray Hawks, and Tropical Kingbirds. Its nearly 57,000 acres are also home to more than 80 mammal species, and some of the few recent jaguar sightings in the United States happened nearby.

Early one morning in August, I met up there with an activist and friend of Silver’s. Tricia Gerrodette is a slight woman of 70 with a graying squall of hair and oval glasses. We talked in the shade near the San Pedro House, a nearly century-old restored ranch that serves as a nexus of SPRNCA’s trail system. The air was heavy from overnight rain. As hikers stopped to wipe mud from their clothes, Gerrodette asked about their sightings, her face lifting with inquisitive warmth at the mention of each bird—seen or hoped for.

Gerrodette isn’t on staff at CBD or any other organization, but fellow advocates say she is critical to their ongoing fights. “She knows the river, knows the policies, and monitors so many different agencies,” says Sandy Bahr, Arizona chapter director at the Sierra Club. While Silver has been successful with a more hard-charging style of activism, Gerrodette’s quiet consistency in the lonelier, unglamorous tasks, such as filing public-records requests, has helped activists stay ahead of encroaching developments.

When Gerrodette and Silver began researching ways to protect the San Pedro in the 1990s, they found that state water law left them few options. Like many states, Arizona observes little legal connection between groundwater and an adjacent river; water users are free to keep pumping even if it drains a stream. This regulatory vacuum has forced advocates to think creatively, shifting their focus toward protecting the river’s dependents, often via the Endangered Species Act. The strategy has worked. Beginning with the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, in 1995, activists have forced the government to list eight species that rely on the San Pedro, tying population declines to dwindling flows and withered riparian habitat, and thus helping to ensure would-be water users don’t cause further destruction. Building cases around those listed species, they’ve won multiple lawsuits against the fort, compelling it to decrease or offset its pumping, often by helping stormwater soak back into the aquifer.

But as more developments have descended on the river, this legal strategy has grown tenuous. In the past two years, Trump officials announced rollbacks to the ESA that, among other things, made it harder to protect critical habitat targeted for development. When I visited, the San Pedro’s advocates weren’t sure what the changes meant for ongoing litigation over the river, especially with lawsuits pending over the rollbacks themselves. (There’s now hope that President-elect Joe Biden’s administration could patch protections back together.) Even so, many had the sinking feeling that, after years of compounding strain, the river was beginning to slip beyond reach. “The ESA has made us all believers in a second chance,” Bahr says. “But sometimes you don’t get one.”

T

he town of Benson, Arizona, sits about 30 miles downstream from Sierra Vista, in a hot lowland valley along the I-10 freeway. A once thriving railroad stop that has dwindled to about 5,000 people, it has been offered new life by a housing proposal that envisions a Tuscan-style village spread atop a nearby scrubby mesa. Watercolor mock-ups for the 28,000-home community, marketed as The Villages at Vigneto, depict golf courses, vineyards, and cobblestone piazzas. The real estate firm financing the build, El Dorado Holdings, run by Arizona Diamondbacks co-owner Mike Ingram, has made a name for itself developing such sprawling desert communities. In Benson, one of the state’s fastest-shrinking towns, the project promises nothing short of a rebirth: as many as 70,000 new residents, $23 billion in economic output, and more than 16,000 jobs.

Vigneto appeared on Gerrodette’s radar in 2014, when El Dorado bought the land and the activists sued to block its Clean Water Act permit. She found the absurdity of it all laughable—Tuscany in Arizona?—but knew the project’s scope was too serious to write off. The issue, beyond its sheer size, was its location: Perched just uphill from the river’s west bank, Vigneto appeared to require razing dozens of tributaries and pumping around 2 billion gallons of groundwater per year. El Dorado maintained that Vigneto would be a “water-sensitive community” that, with low-flow toilets and repurposed rainwater, would use roughly half of what the Sierra Vista area consumes annually.

But in 2016 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers yielded to the activists and suspended Vigneto’s permit pending a consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service about the project’s impacts on endangered species. Later that year, Steve Spangle, a top FWS official in the area, determined that Vigneto’s water use would likely damage habitat for ESA-listed wildlife along the San Pedro and called for a detailed study.

And yet, in late 2018, Gerrodette learned that the Army Corps and the FWS had reversed course, granting the permit without review. She was baffled; in all the years she’d spent investigating developments, she’d never seen a permit reissued without study, much less explanation. The following spring, after filing another lawsuit to challenge Vigneto, she learned that Spangle was claiming he’d been pressured into the decision. Spangle told the Arizona Daily Star that he “got rolled” by his superiors at the Department of the Interior, after David Bernhardt, then deputy secretary, met with Ingram in secret at a Montana hunting lodge. As CNN and other outlets picked up on the story, uncovering additional details connecting Ingram, Bernhardt, and other high-level Trump appointees, Congress announced an investigation. The local activists quickly amended their suit. “This is a clear case of political pressure,” says Stu Gillespie, an Earthjustice attorney representing them. (El Dorado did not respond to a request for comment.)

__________

A source leaked him a previously unpublished 2010 study commissioned by Fort Huachuca, labeled "confidential."

The study was alarming.

__________

In the following months, while Gerrodette continued to investigate Vigneto, Silver searched for more data on water use at Fort Huachuca. As damaging as that future development might be, the Army was still the area’s primary water user. Despite the river’s dwindling flows, the Army’s books showed a balanced water budget year after year. As far as the FWS could tell, the fort was fulfilling its obligation to the river’s endangered species. But as Silver looked into the latest numbers, he stumbled onto some irregularities. When he pressed for details, a source leaked him a previously unpublished 2010 study commissioned by the fort, labeled “confidential.”

The study was alarming. It revealed that pumping had begun harming the river as early as 2003. The fort had managed to project a balanced water budget only by excluding the water it had pumped between roughly 1950 and 2002—a debt of nearly 100 billion gallons. To Silver, the study immediately distilled decades of complex legal battles down to a single fact: Had the Army shared the study with the FWS, as was its legal obligation, the agency never should have concluded, as it had done for years, that the fort could continue operating at its current capacity. In March 2020, CBD, Sierra Club, and the Phoenix-based Maricopa Audubon Society filed suit. (Fort Huachuca declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation.)

To Silver and Gerrodette, the two suits felt like a turning point. For years they’d been fighting to confront Sierra Vista and nearby communities with the reality that they couldn’t grow infinitely with a finite resource. Now, between the apparent interference in Vigneto’s permitting and the fort’s alleged coverup, they appeared to have proved that the river couldn’t sustain such demands. No number of low-flow toilets or aquifer-recharge projects were going to make up for a 100-billion-gallon deficit or 28,000 new homes.

But in spring 2020 the activists were dealt yet another blow, this time from the Trump administration’s new interpretation of the Clean Water Act. Under the rule, developers no longer needed a permit to fill whole classes of water bodies, including ephemeral streams. Still reeling from the ESA rollbacks, the activists now faced losing protections for perhaps all dry stretches of the San Pedro and its tributaries. “If you get rid of the Clean Water Act, you get a race to the bottom,” says Earthjustice’s Gillespie. Save for an intervention by federal authorities—or a favorable ruling among the several lawsuits brought against the new regulations—it seemed Vigneto and the fort were free to treat the San Pedro system’s dry stretches as they would any other ground.

Then in March the coronavirus hit, bringing with it a host of new uncertainties. When I visited the river five months later, Silver and Gerrodette still weren’t sure about the status of their San Pedro lawsuits, much less those against the administration’s rollbacks. But neither felt they could afford to sit still; the implications of the cases had become too far-reaching. It felt as though the river had become a symbol, not only of the Trump administration’s four years of corruption and deregulation, but of how vulnerable these ancient ecosystems were to the whims of a mid-level official or the data in a buried report.

Now some 30-odd years into his fight, Silver is cautious about placing too much hope in the incoming administration. The retired physician likens the river’s survival of the Trump years to a patient living through a near-fatal heart attack. “We celebrate, my god, that we made it through that one fateful night,” he says. But he’s seen enough, on the river and in the emergency room, to know the damage didn’t appear overnight, and recovery isn’t assured.

O

f all the threats to the San Pedro, perhaps the most immediate lies about 15 miles south of Sierra Vista, in the empty desert where the river flows from Mexico into the United States. For months advocates watched with horror as a new 30-foot-high steel-bollard wall marched steadily west toward the river. Gerrodette and thousands of others had gathered in demonstrations at the crossing, angry that the government had waived some 60 environmental and cultural laws, allowing construction crews to decimate Indigenous sites and migratory highways like the San Pedro without review. After years of destructive pumping below the ground, the river was on the cusp of being severed above it, just as it entered the country.

A few hours after meeting Gerrodette at SPRNCA, I drove south to see this wall segment as it neared completion. Thunderheads had erupted in the night, and a brilliant green brushed the ragged foothills. I could just make out the long line of the wall, progressing over the plain toward the river, where it came to a halt. In the last few weeks, as construction crews began laying the wall’s foundation, protesters and hydrologists had warned that—even with gates designed to open in monsoon season—the wall would act as a dam, clogging the channel with floodwater, mud, and debris.

Their predictions had begun to come true. All about the channel, the construction site lay in ruins. Steel casings sat half-buried in earthen rubble, the concrete foundation filled in with mud and branches from the night’s rains. Undeterred by the river’s show of force, a construction crew was already back at work. By mid-afternoon, a crane nosed above the river canopy, clearing the wreckage so the men could begin again.

This story originally ran in the Winter 2020 issue as “The Last Stand on the San Pedro.” To receive our print magazine, become a member by making a donation today.