Last year, two men in Indonesian Borneo noticed a red-eyed bird during one of their daily forest foraging trips. The bird was unfamiliar, so they decided to capture it to take a closer look. Once it was in hand, they snapped some pictures and texted them to a local birdwatching group called BW Galeatus for help identifying it.

An impromptu game of ornithological telephone began. BW Galeatus’s Teguh Willy Nugroho sent the photos to his friend Panji Gusti Akbar, an ornithologist who works with Indonesian birding tour and community science nonprofit Birdpacker. Akbar, in turn, passed the photos on to three more ornithologists. He waited for their verdict, pacing his house in excitement.

One after the other, responses came in: Yes, this was the Black-browed Babbler, a bird last positively identified 170 years ago, well before Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. “When all three replied yes, I just screamed,” Akbar says. “It was quite an amazing moment to be honest.”

Until its rediscovery, the Black-browed Babbler was a “lost” species—it was not officially extinct, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, but hadn’t been documented in the wild for at least a decade. The group Re:wild, a nonprofit that launched a Search for Launch Species campaign in 2017, lists more than 2,000 in its searchable online database. One of the campaign’s regional partners, the American Bird Conservancy, counts between 150 and 200 such lost birds globally, including about 30 in the Americas, that no one has logged on the app eBird in the last decade.

Some lost birds, like the Black-browed Babbler, have only been known from one or two museum specimens collected by long-dead naturalists in little-explored locations. Such species are often rare or hard to detect but not necessarily extinct—especially if no one has actively gone looking for them. For instance, the Damar Flycatcher, native to one small island also in Indonesia, evaded researchers’ notice for more than 100 years until a survey uncovered a thriving population.

At the other end of the spectrum are well-known and documented species that were once fixtures of their landscapes and have now vanished, usually following some combination of habitat loss, hunting, disease, or invasive species introduction. These cases can be more controversial, because it’s hard to prove a species is extinct, and so people hold out hope. For example, many consider the long-lost Ivory-billed Woodpecker, which once lived in the southeastern United States and Cuba, almost certainly extinct. But for others, decades of unconfirmed sightings and elaborate expeditions have kept alive the possibility that the bird lives.

Re:wild launched a global “Search for Lost Species” campaign, in part, to encourage as many people as possible to get involved in the quest in their own backyard. Though it does also facilitate some international expeditions, “this is basically a crowdsourcing project,” says Barney Long, Re:wild’s senior director of conservation strategies. “I really encourage people—if this sparks your interest—to take a look and see what you can do. It’s fun, it’s exciting, and there are loads of opportunities to go out and find a species and save it.”

Among its targeted list of 25 “most wanted” species, six have since been found in the four years since the project launched. These include the Voeltzkow’s Chameleon, found on an expedition in Madagascar in 2018, and the Jackson’s Climbing Salamander, a more serendipitous discovery. The Black-browed Babbler wasn’t on that list or targeted by expeditions, but its surprise rediscovery is exactly the sort of outcome the campaign hopes to inspire.

Similarly, the American Bird Conservancy aims to engage birders—especially those using eBird—to help figure out whether the missing birds are extinct, and, if they are found, protect them before it’s too late. “We have this global community science effort documenting birds around the world,” says director of threatened species outreach John Mittermeier. “It has documented almost all of them, and we have this tiny percentage of birds that is currently missing.”

Targeted searches can also help researchers, community scientists, and locals better understand little-studied regions and gather data on other species that live there. For instance, this year, an expedition to Alto Sinú in Córdoba, Colombia to find the lost Sinú Parakeet uncovered roughly 30 bird species that had never been recorded in the area, along with several that hadn’t been documented in decades. The parakeet, however, is still missing.

Even when searches are successful, rediscovered species still often face an uphill battle to recovery. A whole population might consist of just a handful of individuals pushed into tiny pockets of their former range. A 2011 study surveyed 104 amphibians, 144 birds, and 103 mammals rediscovered in the last 122 years, and found 88 percent of all rediscovered species are threatened with extinction, concluding that they are doomed to “remain on the brink of oblivion.”

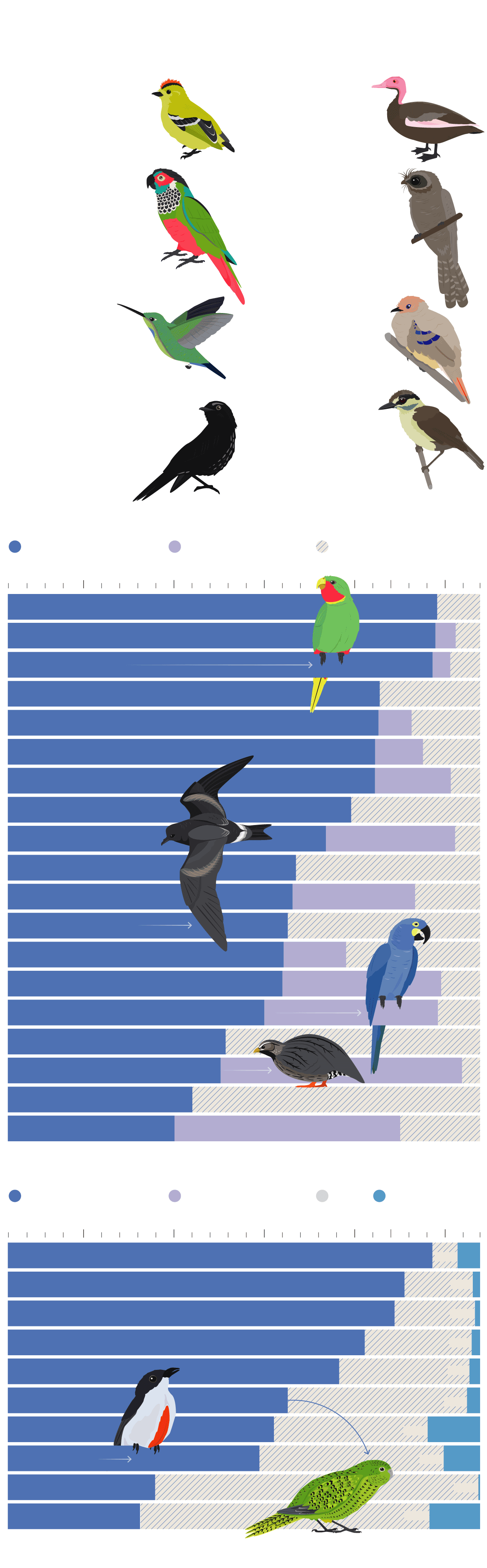

Missing In Action

A sampling of the 150 to 200 birds lost for at least a decade—and 10 that demonstrate why people keep looking.

Pink-headed Duck

Following local interviews that hinted this distinctive duck still lived, a 2017 expedition to find it failed.

Kinglet Calyptura

100 years after this once- abundant bird vanished, the species was found in 1996.

It hasn't been seen since.

Sinú Parakeet

A 2021 search was also the first comprehensive survey of birdlife in Colombia’s Alto Sinú region.

New Caledonia Owlet-nightjar

This mysterious species may persist in remote forests, though searches in the 2000s came up empty-handed.

Turquoise-

throated Puffleg

The 1976 unconfirmed sighting kept hope alive that this hummingbird persists in fragmented habitat.

Blue-eyed Ground Dove

A private reserve and a larger state park now protect the bird’s entire known population.

Black-browed Babbler

A mislabeled museum specimen meant researchers were unsure of this bird’s range until its surprise rediscovery.

Damar Flycatcher

This species was known from a single museum specimen until a 2001 survey found a sizable population.

Lost

Last confirmed sighting

Last debated sighting

Lost

2000

1950

1900

1850

1800

Kinglet Calyptura,

1996

Brazil

Cozumel Thrasher,

1995

‘06

Mexico

Red-throated Lorikeet,

1993

‘02

Fiji

Crested Shelduck,

1964

Korea

Eskimo Curlew,

1963

1981

Canada (Breeding), South America (Wintering)

Bachman's Warbler,

1988

1961

U.S. and Cuba

Semper's Warbler,

1961

2003

St. Lucia

Sinú Parakeet,

1949

Colombia

Pink-headed Duck,

1935

2006

Myanmar

Rück's Blue Flycatcher,

1918

Sumatra

Cayenne Nightjar,

1917

1982

French Guieana

Guadalupe Storm-petrel,

1912

New Caledonia

New Caledonian Buttonquail,

1911

1945

Brazil

New Caledonia Owlet-nightjar,

1910

1998

New Caledonia

Glaucous Macaw,

1800s

1997

Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay

Jamaican Petrel,

1879

Jamaica

Himalayan Quail,

1876

2010

India

Jamaican Pauraque,

1860

Jamaica

Turquoise-throated Puffleg,

1850

1976

Ecuador

FOUND

Last confirmed sighting

Last debated sighting

Lost

Rediscovery date

2000

1950

1900

1850

1800

Madagascar Pochard,

1991

2006

Madagascar

Belem Curassow,

1978

2017

Brazil

Antioquia Brushfinch,

1971

2018

Colombia

Táchira Antpitta,

1956

2016

Venezuela

Blue-eyed Ground Dove,

1941

2015

Brazil

Night Parrot,

1912 (last live sighting)

2013

Australia

Cebu Flowerpecker,

1906

1992

Philippines

Damar Flycatcher,

1898

2001

Indonesia

Black-browed Babbler,

1840s

2020

Borneo

Pelzeln’s Tody-tyrant

1831

1992

Brazil

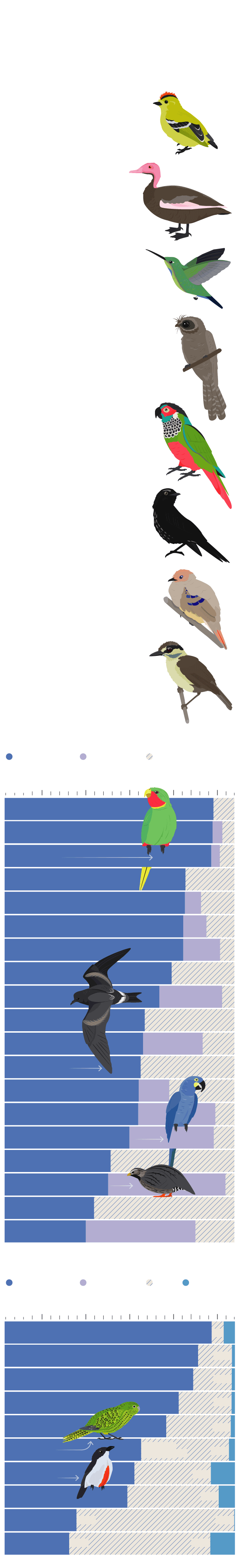

Missing In Action

A sampling of the 150 to 200 birds lost for at least a decade—and 10 that demonstrate why people keep looking.

Kinglet Calyptura

100 years after this once-abundant bird vanished, the species was found in 1996. It hasn't been seen since.

Pink-headed Duck

Following local interviews that hinted this distinctive duck still lived, a 2017 expedition to find it failed.

Turquoise-throated Puffleg

The 1976 unconfirmed sighting kept hope alive that this hummingbird persists in fragmented habitat.

New Caledonia Owlet-nightjar

This mysterious species may persist in remote forests, though searches in the 2000s came up empty-handed.

Sinú Parakeet

A 2021 search was also the first comprehensive survey of birdlife in Colombia’s Alto Sinú region.

Damar Flycatcher

This species was known from a single museum specimen until a 2001 survey found a sizable population.

Blue-eyed Ground Dove

A private reserve and a larger state park now protect the bird’s entire known population.

Black-browed Babbler

A mislabeled museum specimen meant researchers were unsure of this bird’s range until its surprise rediscovery.

Lost

Last confirmed

Last debated

Lost

sighting

sighting

2000

1950

1900

1850

1800

Kinglet Calyptura,

1996

Brazil

Cozumel Thrasher,

1995

‘06

Mexico

Red-throated Lorikeet,

‘02

1993

Fiji

Crested Shelduck,

1964

Korea

Eskimo Curlew, Canada (Breeding),

1963

‘81

South America (Wintering)

Bachman's Warbler,

1961

1988

U.S. and Cuba

Semper's Warbler,

1961

2003

St. Lucia

Sinú Parakeet,

1949

Colombia

Pink-headed

1935

2006

Duck, Myanmar

Rück's Blue

1918

Flycatcher, Sumatra

Cayenne Nightjar,

1917

1982

French Guieana

Guadalupe Storm-

1912

petrel, Mexico

New Caledonian Buttonquail,

1911

1945

New Caledonia

New Caledonia Owlet-nightjar,

1910

1998

New Caledonia

Glaucous Macaw, Argentina,

1800s

1997

Brazil,Paraguay, Uruguay

Jamaican Petrel,

1879

Jamaica

Himalayan Quail,

1876

2010

India

Jamaican Pauraque,

1860

Jamaica

Turquoise-throated

1850

1976

Puffleg, Ecuador

FOUND

Last confirmed

Last debated

Lost

Rediscovery

sighting

sighting

date

2000

1950

1900

1850

1800

Madagascar Pochard,

1991

‘06

Madagascar

Belem Curassow,

1978

2017

Brazil

Antioquia Brushfinch,

1971

2018

Colombia

Táchira Antpitta,

1956

2016

Venezuela

Blue-eyed Ground

1941

2015

Dove, Brazil

Night Parrot,

1912 (last

live sighting)

2013

Australia

Cebu Flowerpecker,

1992

1906

Philippines

Damar Flycatcher,

1898

2001

Indonesia

Black-browed

1840s

2020

Babbler, Borneo

Pelzeln’s Tody-

1831

1992

tyrant, Brazil

Still, looking is worth the effort—even for long shots. “I think that every species deserves its chance,” Long says. “The whole point of these searches is to find the rarest of the rare and catalyze conservation actions for them.” Such efforts can also lead to renewed interest in protecting vulnerable regions, as was the case for the Blue-eyed Ground Dove. Brazilian ornithologist Rafael Bessa rediscovered this striking bird in 2015 after it had gone unseen for 75 years. The news brought more attention to Brazil’s highly endangered cerrado ecosystem—just three percent of which is currently protected. Within a few years, the bird’s tiny wild population was contained within a small private reserve and a larger state park.

Akbar hopes that the Black-browed Babbler rediscovery will similarly lead to more conservation and research efforts in the area where locals found it. In May, he was coordinating with the Indonesian government to plan a trip to the site with other ornithologists, and he’s eager to get there himself. “It is exciting, but also kind of frightening, because we don’t know how well they are doing out there,” he says. “We don’t know about its habitat, habits, or threats.” The babbler’s rediscovery is also a testament to how unexplored some parts of Indonesia still are, he says. “Who knows, there might be even more discoveries waiting to happen."

This story originally ran in the Summer 2021 issue as “In Search of Lost Birds.” To receive our print magazine, become a member by making a donation today.