Tucked away in the art room of the National Audubon Society’s New York City office lies a treasure trove: nearly every single issue of the organization’s magazine ever published, bound in thick volumes. Before I began my editorial fellowship in January 2024, I didn’t know Audubon magazine dated all the way back to 1899, when it was first printed under the name Bird-Lore. Soon, I would become somewhat of an expert on these records.

My fellowship turned out to coincide with the magazine’s 125th anniversary. In my first week, I sat with the editorial team flipping through old issues, trying to find themes and interesting angles to celebrate the milestone. We mused about antiquated birding advice, were charmed by endearing old letters from readers, and learned how pivotal moments in history shaped the magazine’s focus.

It was an eye-opening experience, especially as an early-career journalist who’s long been fascinated with birding culture. Birders, in some ways, have changed little since the early 20th century. Many things felt familiar: Jokes about the personality quirks of birds such as the Ruffed Grouse. Spirited debates about photography ethics. The awe of seeing a Northern Gannet colony. And yet, so much about the world has changed, whether the technology at our fingertips or our growing footprint on our environment.

As our team formulated a plan to capture this body of work, I took on the task of cataloging each issue’s cover—its subject, photographer or illustrator, location, and more. With no digital archive of the magazine prior to the mid-2000s, our idea was to get a snapshot of what was deemed cover-worthy through the years. A straightforward exercise. We thought it might take a couple of days.

Yet starting with the very first issue of Bird-Lore, time began to slip away. After a week, when I reached the 1950s (or was it the ‘60s?) the decades blurred, then shape shifted. Black-and-white covers burst into full color. Dispatches from yards and local parks became longer features about habitat destruction and conservation—first mostly across the country, then around the world.

More than 700 entries later, we not only had a database of Audubon’s covers, but I also came away with a deeper understanding of how environmental journalism and the broader conservation movement has evolved. Throughout, birds bonded people together, inspired art, and compelled us to think critically about our connection to the planet. Here’s what we found.

Introduction

Between 1899 and 2024, Audubon (dating back to its beginnings as Bird-Lore) published more than 730 issues—and we catalogued the covers of nearly all of them. Birds, of course, featured prominently. We counted at least 243 identifiable avian species, with bird subjects appearing a total of 487 times. The magazine also showcased plenty of other wildlife and their habitats: Mammals graced our cover 79 times (representing at least 46 different species); fish, insects, and other animals, 25 times; specific plants, more than 50 times, and landscapes, more than 70 times.

Here, we illustrate these data in two ways—on the left, how broad categories of wildlife and their environments showed up over time, and on the right, the how those categories break down into species (circle size represents frequency).

Songbirds Galore

Songbirds were, by far, the most well-represented group of birds on the magazine’s covers, with more than 170 appearances. They were showcased especially frequently in the early years, when encouraging the emerging hobby of birdwatching and bird feeding as a catalyst for conservation was a major focus. As a result, backyard birds and other common species like the American Robin and this Eastern Kingbird (pictured, with its young) were often in the spotlight.

First Cover: Horned Lark

Bird-Lore’s first cover, on its February 1899 issue, features H.W. Menke’s image of a flock of Horned Larks on a snowy field. Inside the issue it accompanied Menke’s story of wintery bird observations from a cabin in Wyoming, including his attempts to photograph birds from his window. Horned Larks, a common species, were featured five more times on the magazine’s cover, all before 1920—but never again since.

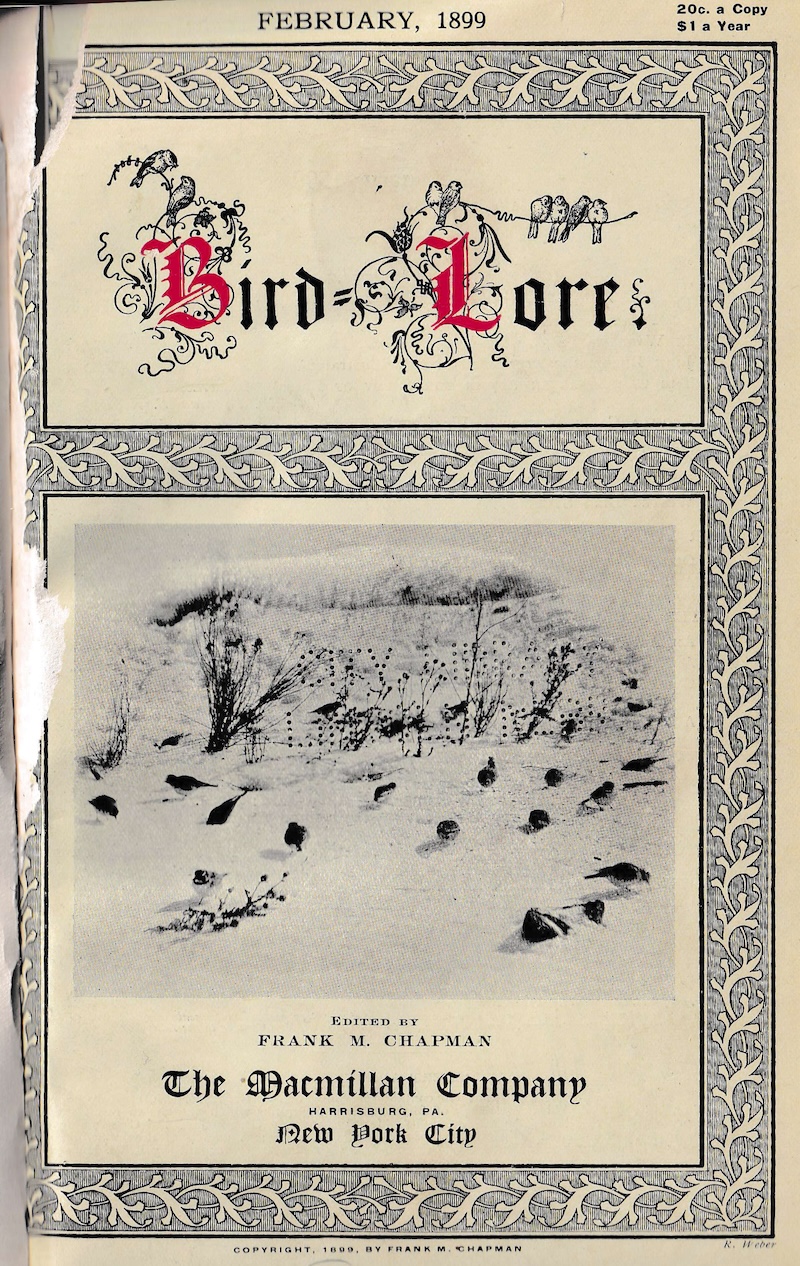

Top Bird: Great Egret

By the late 1800s, plume hunters had nearly wiped out Great Egrets and many other wading birds. The National Audubon Society formed in 1905 to campaign for these birds’ protections, and in 1953 declared the Great Egret its symbol. Over the years, the bird appeared on the magazine’s cover 12 times, the most of any species. Great Egret covers often celebrated Audubon anniversaries, but they also illustrated stories of wetland conservation in places like Florida's Everglades and South America’s Pantanal.

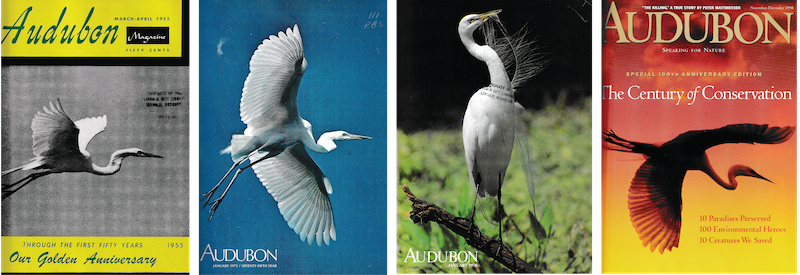

Top Bird: Bald Eagle

Another symbolic species proved a close runner up, appearing 11 times. The Bald Eagle first graced the cover during World War II as an emblem of patriotism. It showed up again soon after, associated with a 1948 article about “Eagle Man” Charles Broley, whose work banding the birds helped sound early alarms on DDT—a concern also featured with a Bald Eagle cover in 1960. And in 2006, we celebrated the species’ “robust” comeback with a cover image of “Challenger,” a nationally beloved eagle mascot, just before the bird was removed from the endangered species list.

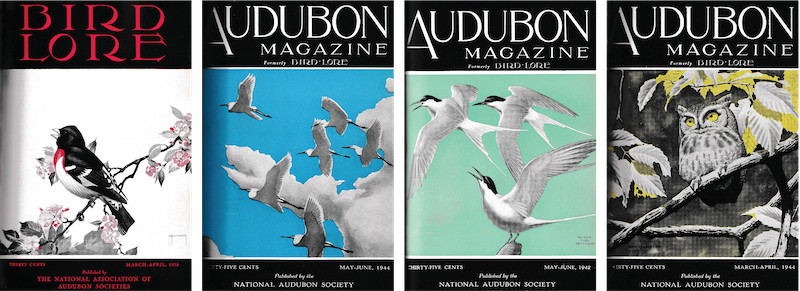

New Nameplates

Ornithologist Frank Chapman created Bird-Lore as a bi-monthly magazine “devoted to the study and protection of birds.” From the start, it connected members of the growing movement of Audubon societies as their official publication, and in 1935, the National Audubon Society formalized the relationship by purchasing it from Chapman. A 1941 issue featuring White-tailed Kites was the first with the name Audubon Magazine, and in 1961, on an issue featuring mule deer, the “Magazine” was dropped to become simply Audubon. As the magazine evolved over the years, the visual aesthetic also morphed: The nameplate featured a range of typefaces, from elaborate gothic lettering in the 1920s to a looping hand-written one in the ’60s to the thinner serif font used today.

Illustrated Era

In the decade after the 1935 change in ownership, the magazine began featuring illustrated covers, a major shift from black-and-white photos. This era showcased art from such luminaries as Don Eckelberry and Roger Tory Peterson, who illustrated 42 covers (and also served as the magazine’s art director). To keep costs low—a year’s subscription was $1.50—these illustrations were limited to two inks: black and a single color. Sometimes, that color was strategically deployed to highlight a bird’s field marks, like the red throat of a Rose-breasted Grosbeak; other times, it served as the background. (Per a 1942 profile of Peterson, “gaudy morsels” such as the Painted Bunting were out of the question.)

Image Evolution

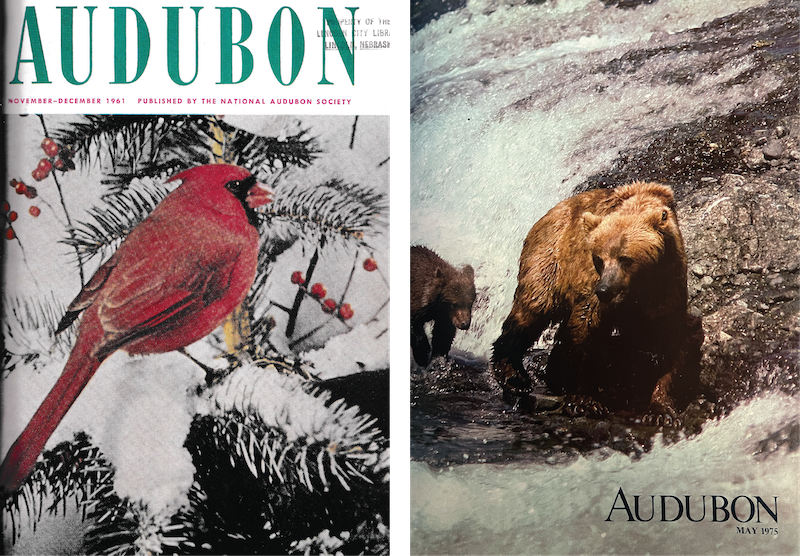

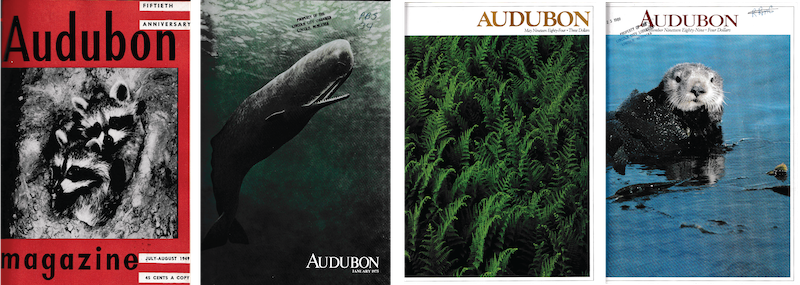

Chapman said the magazine he created would print the best photographs of living birds ever published in the United States. Limited by camera technology, a number of early 20th century covers depicted tame, captive, and nesting birds. Depictions of birds in their natural habitat became more varied as gear improved—eventually evolving into sharp pictures of avians in action. Decreasing color printing costs and other innovations also helped: The Kodachrome image of a Northern Cardinal on our 1961 issue marked one of Audubon’s earliest color photo covers. In 1975, the magazine was the first major national publication to use a technique called screenless lithography, printing a richly detailed brown bear.

A Wider Lens

Starting in the 1950s, birds, shockingly, mostly disappeared from Audubon’s covers. Instead, racoons, whales, otters, and other wildlife, along with landscape photography, stole more of the scene. This reflected the evolving focus of both the organization and magazine, as a greater awareness of the interconnectedness of nature took hold. Stories on the natural history of wildlife, as well as broader tales of habitat protection and environmental destruction, figured more prominently, especially under the long-time leadership of editor Les Line beginning in 1966. It wasn’t until 2012 that birds would return as a consistent presence.

And the Winner is...

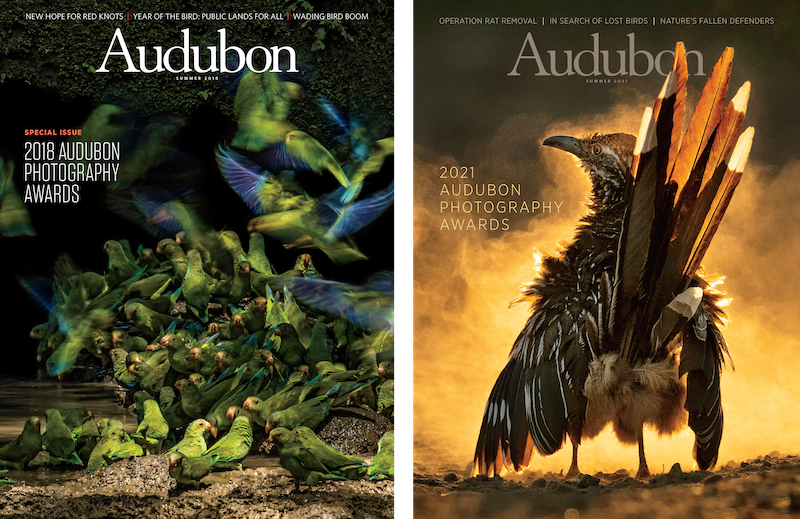

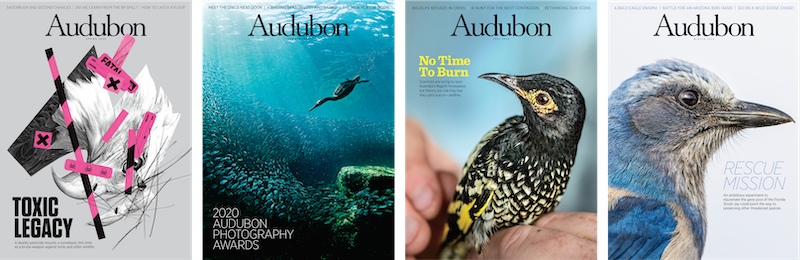

In 2010, Audubon held its first modern photo awards and featured the winning image of a Bald Eagle on its cover. Since then, cover-worthy honorees have included a chaotic flock of Cobalt-winged Parakeets in 2018, a Greater Road Runner dust-bathing in 2022, and for this, the contest’s 15th year, a pair of dueling Blackburnian Warblers. The annual issue featuring these stunning images, alongside the stories of how they were captured, has become a reader favorite.

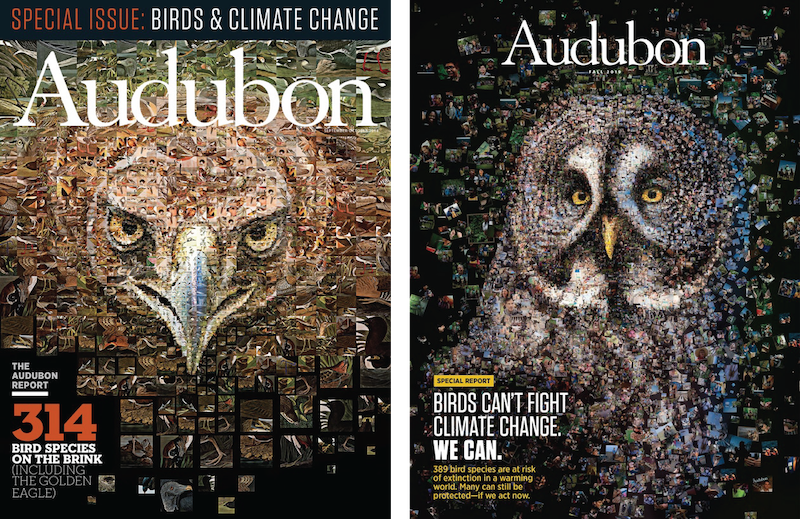

Climate In Focus

In September 2014, Audubon published a special issue on climate change starring the Golden Eagle. A closer look reveals a collage comprising hundreds more birds, representing the 314 climate-threatened species highlighted that year in Audubon’s groundbreaking Birds and Climate Report. In 2019, when Audubon updated these findings in its Survival by Degrees report, the data pointed to 389 bird species at risk of extinction from climate change. The magazine again featured an avian mosaic, spotlighting the Great Gray Owl. But this time we leaned into people power: Visual designer Charis Tsevis incorporated 403 images of Audubon volunteers and staff taking action.

General Excellence

As the global pandemic unfolded, 2020 marked a year of hardship, adaptation, and seeking respite where we could. Audubon focused on covering the challenges our community faced while aiming to help readers find joy in birdlife and nature. Our print and digital coverage that year led to the prestigious National Magazine Award for General Excellence. Audubon’s writers, photographers, artists, editors, designers, and all of our collaborators raised the bar well beyond what seemed possible—and continue to do so. As of 2024, our unprecedented run of nominations in this category has remained unbroken.

Finally, below, are subjects appearing on all Audubon issues that we catalogued. To create this chart, we used the wildlife names as described in caption information at the time of publication. We generally add the descriptor “(unknown)” if a specific species or common name was not provided in the caption for wildlife and plant subjects.

Get Audubon in Your Inbox

Let us send you the latest in bird and conservation news.